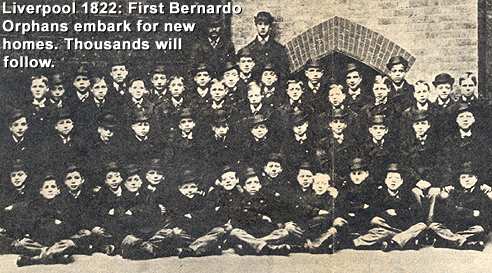

A photo exhibit touring the country is a reminder of the

100,000 orphans shipped to Canada as part of "God's work."

BY Greg Smith

In 1921 Len Austin decided to emigrate. Sitting with the other boy’s of an orphan’s home in England, Austin has listened eagerly to the officious-looking gentleman who concluded his talk with the magic question: "Now then ", who's for Canada?" His hand shot up to pluck the promises of idle hours, sleigh-rides, horseback riding, ice skating, ice cream and cake. Austin didn't mind much that his two older brothers were staying behind. He knew what he was doing. He was 5 years old.

Len Austin was a Barnardo boy, a product of one of the most highly regarded philanthropic agencies in England. When he finally stepped off the ship in his new country 100 other boys who had made the same decision were eagerly following behind. All were part of a unique immigration scheme that from 1869 to the late 1930s brought at least 100,000 children, aged 5 to 16, into Canada. Twenty-five thousand were Barnardo boys and girls. Most were orphans like Austin. In the early years they came from the streets and alleys of London's East End - homeless, destitute, often delinquent unwanted wards of a society that offered little child care and a great deal of exploitation. Later, these street arabs were supplemented by children of impoverished families who were looking for a way out.

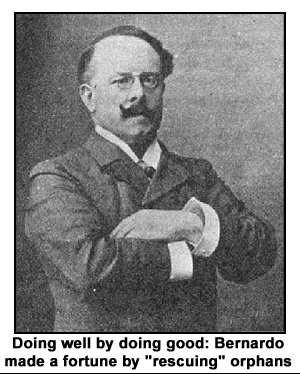

Thomas John Barnardo became obsessed with the plight of London's growing child pauper population while studying at-London Hospital. Forgoing plans to become a medical missionary in China, the young doctor opened his first home for boys at Stepney Causeway in 1970 and had cared for more than 60,000 children by 1905 when he died. Besides food and shelter, Barnardo provided schooling and training for his wards, his ultimate goal being to place them to work in good Christian homes.

Canada was young, sparsely populated and in dire need of labour. The cost of maintaining the children in England was enormous. Steam passage to the colonies was cheap. And, most important the Canadian government wanted these children badly. "I can remember people coming to sort of pick you out", says Austin. "You know, do you want this boy or that boy. They'd size you up as if you were a little heifer going to market. If they thought you looked promising, you were sort of signed up with them and away you went.

The Canadian government offered a $2 bonus for each child brought over. Provincial authorities helped by providing transportation subsidies and even local governments pitched in, offering grants and tax-free housing facilities. And there were waiting lists for child. Although child emigration began in 1869, Canada instituted no regulations or follow-up inspections until 1888.

"We kept a package of homes oh, I would say about 100 or so, on the go all the time", recalls Hattie Glover, 95, who worked most of her life for Barnardo at her receiving home for girls in Peterborough, Ontario. Besides his Hazel Brae Home for Girls in Peterborough, Barnardo maintained a Canadian headquarters in Toronto, receiving homes on Jarvis Street – Toronto, Pacific Avenue in Winnipeg, and a training farm for older boys in Russell, Manitoba.

Isaac Harrison immigrated, with a Barnardo group in 1914, when he had just turned 15. He was placed with an elderly couple who ran a greenhouse in Orangeville, Ontario. "You were put out for so much for three years, you see," says Harrison, who now lives in Peterborough, Ontario. "All I got was $100 for three years. You got your board and clothes the first year, $40 your second and the third year you got $60. But you didn't receive that until you were 21. When you left there after three years you got $25."

Harrison wasn’t an orphan. He was put into a Barnardo home when he was 8, after his father died leaving his mother with seven children to raise. "They gave you good training there and kept you in your place," he remembers. "Then when I was 15 they asked if I wanted to come to Canada. What would you do? They tell you this is the land of milk and honey when you’re a kid. It wasn’t."

After his three years at the Orangeville greenhouse, he says, "I didn't stay there. I just cleared right out altogether. I went to a farm outside Orangeville and stayed there three or four years and during the next seven or eight years just worked for different people. I was treated all right at the first place. Not overly good but fair. Oh 'I've seen some kids that were really, knocked around. Some got a really good home and some didn't'

Len Austin was in this latter category. Coming at the age of 5 he was too young to object to anything that would happen to him. He recalls running away from his first placement but isn't quite sure of the reason. "It’s hard to say. I think I was likely abused or something. I don't know for sure because it happened to me afterward and I ran away again so I imagine it happened in the first place." His next home was a happier one. "I really enjoyed living there. They were very poor and had nothing but they were nice to me. But it was dirty and infested with flies." The inspectors decided the environment wasn't healthy for a young boy and they took him away. "I can remember bawling about that," he says.

The next eight years he spent on a 150-acre farm in the St. Lawrence valley. "When I got home from school," he recalls, "I had to get right down and milk so many cows, or else. Same in the morning, before I went to school, I had to milk the cows and clean out the barn. If it wasn’t done right I got a beating. The farmer had two sons and they worked too, but I had to do all the worst stuff. Then after Grade 8, I was pulled out of school and became more or less the hired hand. The other boys were off to college and I had to do everything.

The inspectors visited about twice a year but you couldn’t tell them much or else you’d get beat up more. You know I even didn’t eat with the family. I eat in the back kitchen with the dog."

Austin was pushed to the extreme. "I was so young and trying to work as a hired hand and not being able to do it. One time we were loading grain and I couldn't keep up. He'd yell 'H'raw, h’raw, c’mon, c’mon, and then all of a sudden I’d see a fork tyne going by my face. I was standing up and just grabbed it like a baseball bat and hit him across the back as hard as I could. He was screaming. I started climbing down and just when I got to the bottom this other guy was coming in. He asked me where the old man was, I just killed him." He ended up in bed for five weeks-

When he was about 15 Austin finally ran away and sought refuge with one of the boys down the road. He was older and worked for another farmer. The old man came looking for me and this boy, he was pretty husky, told him to get back in his car and never bother me again or else he'd push his head in the gravel. And that was where it ended." Austin went on his own, working as a hired hand with various farmers. He never received any money for his eight years labour. "The last year 1 was supposed to get $180 but I ran away and didn't see any of it."

Rose Menzies landed in Peterborough in 1921 when she was 16. Her story is a happier one. "We stayed up at Hazel Brae until we were placed where we were supposed to go. I was working as a domestic. I had my own room and they were very good to me. Of course, I did all the work - the mistress never worked a day in her life - but that was all right. They paid me $14 a month, that's what I started at. When I left I was making $20."

In England she had been in a Barnardo home since she was 4. "You went to school until you were 14 and. then they trained you for domestic work. Coming to Canada was exciting. They fed us really well on the ship and there was a doctor along to take care of us. I remember us girls laughing at the funny clothes the boys wore here in Canada. And the train was the funniest thing we had ever seen. with bells on and rows of seats instead or compartments."

Relocating 25,000 children was an immense project requiring painstaking painstaking organization and, of course, a considerable amount of money. All Bamardo's children spent time in homes in England before they were sent out to Canada. To finance his philanthropy Barnardo to the public, touring England and passionately presenting his ideals against a backdrop of carefully selected lantern slides and an assortment of pamphlets and books. He soon grasped the potential of photography and compiled an awesome photo library that contained a record of every child that walked through his doors. He used these pictures brilliantly, establishing a kind of early before-and-after testimonial. He doctored his models, of course, keeping suits of rags alongside clean-pressed trousers in his studio. But the effect was stunning, and the penny postcards he sold proved invaluable.

As propaganda his booklets are a match for any present-day hard-sell. One classic entitled "Two Rescues" recounts a "true life story" about an adoption in Canada. Little Jenny, whom Barnardo found in the vile environment of women whose open degradation made them conspicuous even in the abode of dragons" is taken away. In doing so, however, Bamardo admits, 'I had not quite covered my tracks," A "relative" appears to reclaim her, but Barnardo resolutely ships her off to Canada, where she is adopted by a typical rough. homestead family who don t speak to her until the evening dinner when Jenny fearfully puts her hands together for a thanksgiving prayer. The family breaks into tears and asks her to repeat the prayer so they can pray along with her. She is accepted with hugs of joy and ultimately leads the burly Canadians back to God.