8.† Change is more easily effected by reducing the

forces

against change than by strengthening the forces for it.

Situations

involving change can be analyzed by looking at the forces

for and against

change that tend to balance out and keep activity

at a given level.

Consider the university professor in a publish-or-perish

atmosphere.

Publishing more may mean a promotion, recognition,

and the

satisfaction of owning part of a book or journal.

Yet a number of

factors balance these forces, such as the solitary

nature and

loneliness of writing, the knowledge that relatively few

people ever read

professional journals, the ease with which writing

can be postponed,

and the possibility of not being published. Considering

the balance of these

factors, the professor will probably

write about one

article every year or two.

This force-field

analysis can be pictured as a giant tug-of-war,

with the supporting

forces pulling on one side and all the

restraining forces

pulling on the other. In a force field related

to my smoking

behaviour, the restraining forces easily overpower

the supporting

forces and I donít smoke, although a couple of

times sustaining

forces increased and I actually considered smoking.

One of my

associates smoked between one and two packs a day,

depending on the

balance of his forces at any moment. If tension

increased and other

smokers arrived, etc., his smoking increased; if

we were alone and

he was busy driving the car or washing dishes,

his smoking

decreased. Thus the balance is not static or routine

habit but dynamic,

changing with the balance of forces. Recently,

he had a heart

attack, and reluctantly, he quit smoking.

I have saved this

assumption about change until last because of

all the concepts

from the social sciences, I have used this one most

frequently and with

the most success. Most of my consulting work

has involved a

group doing a force-field analysis and then planning

specific strategies

to reduce the restraining factors of the proposed

change. In my early

days as a student counsellor and now in my

executive coaching,

the force field was and is used to assess the

pros and cons of

any action being considered. Exploring the

question ďWhat is

the worst thing that could happen?Ē clarifies the

fears and blockages

and frees the way to constructive planning for

managing these

problems.

Going back to the

tug-of-war analogy, increasing the supporting

forces would be

like adding more members or stronger ones to that

side of the rope.

The other team will now have to resist harder,

dig their heels in,

or lie down in their effort to hang on. However,

if one side stopped

pulling and let go of the rope, the other side

could no longer

resist ó there would be nothing to pull against.

Rather than arguing

about the pros and cons of a particular action,

the merits of both

sides are discussed and the feasibility of the proposed

action is further

tested by having both sides strategize how,

if at all, they

could reduce the restraining forces. If they are successful

in figuring out how

to remove or reduce the blockages, the

proposal will be

free to move forward.

This dynamic

suggests that in getting ready for an initiative,

the promoters will

profit from doing an analysis of the change program

using a force-field

approach and then considering ways of

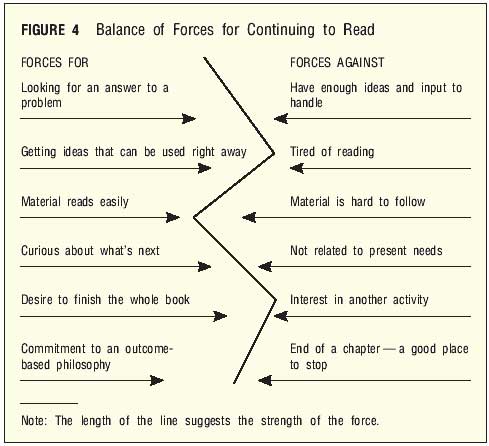

reducing the factors against the change. Figure 4 depicts one possible

force-field

analysis of whether or not you will finish reading this

book. Depending on

how the forces balance for you, you will stop

reading, read a bit

more, or read a lot more. The wavy line in the

middle tries to

highlight the idea that the balance of forces may be

continually

shifting. The balance at this moment is that you will

continue reading,

but in five minutes the notion of a hot or cold

drink may get to

you and youíll stop. In a complex social system,

it is likely that

the balance of forces has set a pattern that has

become

institutionalized and will be much harder to change.

Now that we have

looked further into the process of managing

a program

development initiative and the assumptions about handling

the changes it will

trigger, letís assess your organization and

its readiness for

an initiative.

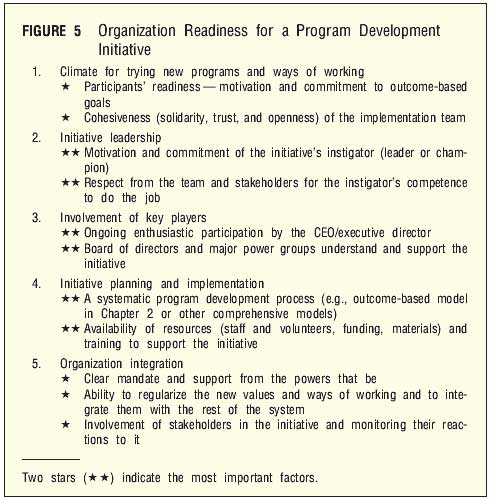

When I first began

the program development model, I had

established a

number of factors to be used to assess an organizationís

readiness (see Figure 5). Over the years these key factors of

an organizationís

readiness for a program development or organizational

improvement

initiative have been refined a bit to make up

a survey that

predicts the likely success of the initiative. While

I donít have a lot

of data from controlled studies to establish

its validity, it

does reflect my own experiences. These experiences

include eight

summers on staff in three different camps; resident

master of a

residential school for physically disabled boys; director,

Department of Group

Guidance, Montreal Childrenís Hospital;

coordinator of

staff development and training, Montreal YMCA;

teacher and leader

of adult training programs at 13 universities

in

400 nonprofit

(community-serving and government) organizations.

I report these

experiences to indicate where I am coming from

as an author and to

give some credibility to the survey shown in

Figure 6 - click here.

The above

discussion and the survey shown in Figure 6 assume

that the

outcome-based program development initiative will focus

on modifying and

changing the existing culture of the organization.

The success or

failure of the initiative will therefore depend on

whether or not the

agency adopts the new values and ways of

working of the

outcome-based model. However, there is an alternative

to trying to change

existing values and ways of working that is

well worth

describing, as it has been very successful in some of my

experiences.