|

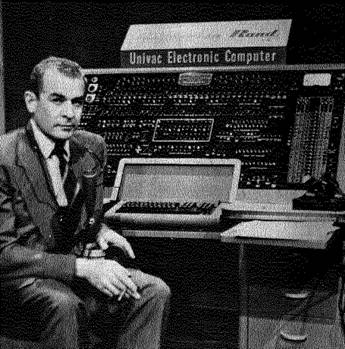

UNIVAC Becomes a Household

Word A reading from Harry Wulforst's 1982 book BREAKTHROUGH TO THE COMPUTER AGEScanned by jds 1991 on Logitech 4" hand held scanner then OCRed with bundled software all at a cost of about $400.

The red light on the television

camera clicked on. Charles Collingwood, seated in a CBS studio in New York

City, smiled confidently at his unseen audience across America as he revealed

the network's plans for broadcast coverage of the 1952 presidential election:

"Here at CBS we are making elaborate preparations to bring you the results

of the night of November 4th, just as quickly and as accurately as is humanly

possible. Matter of fact, we want to bring them to you faster and more

accurately than is humanly possible, so we have enlisted the aid of Remington

Rand's UNIVAC.... If UNIVAC behaves the way we think it will, we'll all know

the winner long before the final votes are counted."

During the weeks preceding

Collingwood s announcement, political

analysts, statisticians, and computer programmers had huddled in meetings in

Philadelphia conjuring up ways to endow UNIVAC with sufficient expertise to

predict the winner of the Eisenhower‑Stevenson race after only a small

portion of the votes had been tallied. Months earlier, when UNIVAC was first

brought to the attention of CBS, the experts at Remington Rand had blithely

assumed that programming the system for analyzing voting patterns across

America would be a routine undertaking. However, as the weeks

rolled by and

the election night

deadline loomed ever closer, the experts thought that they had bitten

off more than they could chew.

It had started as a simple

business barter arrangement. In April 1952 a representative of the network had

come to Remington Rand with a proposition. The office equipment manufacturer

would be given nationwide television exposure at no cost in return for the

temporary use of a hundred or so typewriters and adding machines. The quid pro

quo was to be part of the programming: As television cameras panned around the

huge studio (which would be filled with workers diligently tapping the keys of

adding machines and typewriters), a camera

would zoom in

over someone's shoulder from time

to time to focus briefly on the Remington Rand logotype emblazoned above the

keyboard. The deal was sealed with a handshake, but before the CBS man reached

the door, a suggestion by a Remington Rand publicist stopped him in his tracks.

Sustaining viewer interest

during the tedious hours of reporting the vote, precinct by precinct and state

by state, was a tough challenge for broadcasters. Break the monotony, said the

publicist, by predicting the winner with an electronic computer and viewers

will stay with you all night to see if the computer is right or wrong. This

extra bit of show biz, which might possibly add some life to a slow-moving

story, was enthusiastically endorsed by CBS management, but

professional newscasters did

not know whether to take the

matter seriously or not. Their general uneasiness was evident in a response by

Walter Cronkite (then chief Washington correspondent for CBS) to a question by

Dorothy Fuldheim during an evening news broadcast by WEWS‑TV in

Cleveland, Ohio:

DOROTHY FULDHEIM: Tell me, Walter, what are you going to do to

report this very historic election? WALTER CRONKITE: Well, this year we've got the

same basic formula that we had before, which is, of course straight reporting

of how the returns are coming in. However, we do have a little gimmickry

this year which I think is most interesting, and may turn our to be something

more than gimmickry. We're using an electronic brain which a division of

Remington Rand has in Philadelphia. DOROTHY FULDHEIM: What does it do? WALTER CRONKITE: It's going to predict the outcome of the

election, hour by hour, based on returns at the same time periods on the

election nights in 1944 and 1948. Scientists, whom we used to call long hairs,

have been working on correlating the facts [for these predictions] for the past

two or three months. . . . Actually, we're not depending too much on this

machine. It may just a sideshow...

and then again it may turn out be of great value to some people.

At the time Cronkite was telling

Dorothy Fuldheim that UNIVAC might be of great value, the long hairs in

Philadelphia were fearful that its widely publicized debut on television would be a flop. Before

UNIVAC could be programmed

to rapidly analyze

the election night

returns, mathematical equations had to be formulated describing trends

and voting patterns for thousands of political sub‑divisions throughout

the United States. This massive undertaking was rendered more difficult by the

fact that there was virtually no precedent for an analysis of this magnitude. The statisticians, labouring over reams of

data covering the two previous presidential elections, had no existing body of

expertise to guide them.

Finally, a workable method for

processing the data gradually took shape. Now the experts could direct their

attention to the practical business of getting ready to run the problem when

the returns started coming in. Because

the only available UNIVAC systems were in Remington Rand's factory in

Philadelphia, a special Teletype line was reserved for transmitting the vote

counts from CBS election night headquarters in New York. Three UNIVAC systems figured in the plan: One to actually

process the data and be seen on television; a second UNIVAC, behind the scenes

to carefully check the output of the

first; and a third, on standby, in the event of an emergency.

called out on a

printer. Then the latest total

for that precinct was located on

the original Teletype and the correct count re-entered into the system, which

produced a validated listing on a fourth reel of magnetic tape.

While the most recent tallies

were being transcribed on the fourth tape, all of the precinct totals were

sorted into a predetermined sequence. At the same time, the data were subjected

to three additional tests. First, the number of districts reporting was checked

against the total number of districts in the area under study. Second, the

reported vote on any given pass had to be at least as high as the previously

reported total. And finally, the major party votes in each district were

compared with similar data compiled for that constituency in 1944 and 1948.

The vote totals were then in the

proper format for entry into the primary UNIVAC system. For this phase,

composite analyses of returns in the 1944 and 1948 elections had been stored in

the computer's memory in addition to a comprehensive history

of state‑by‑state voting

trends dating back to 1928. From

this information district profiles were charted that defined the relative

strengths of the major party registrations and the so‑called independent

vote.

The district totals fed into

UNIVAC's processor from the fourth tape were compared to the historical records

of those districts in the computer's memory. Then a final vote probability was

determined for each locality. These voting patterns became the basis for a

general preliminary estimate of the total national vote for each candidate.

Adjustments were then factored in at prescribed intervals to correct any

discrepancies that arose between the actual vote counted for a district and the

voting pattern selected for that district. In this way as the evening wore on and larger percentages

of the total vote cast could be fed into the system, each subsequent projection

could be based more on hard facts and less on assumptions.

By 9:00 p.m., with early returns

streaming in from the eastern and central time zones, the huge CBS election

night headquarters in New York City was buzzing with activity. Telephones jangled.

Teletype machines clacked

noisily. Scribbled figures on scraps of paper were passed hastily to

toteboard operators. Then the director in the control room, scanning an array

of monitors, barked an order. Instantly the face of Charles Collingwood flashed

on screens in living rooms across the nation as the comforting voice of Walter

Cronkite told viewers what was going on.

WALTER CRONKITE: And now to find out what perhaps this all

means, at least in the electronic age, let's turn to that electronic brain,

UNIVAC, with a report from Charles Collingwood. COLLINGWOOD: UNIVAC, our

fabulous mathematical brain, is

down in Philadelphia mulling over the returns that we've sent it so far. A few

minutes ago, I asked him what his prediction was, and he sent me back a very

caustic answer. He said that if we continue to be so late in sending him

results, it's going to take him a few minutes to find out just what the

prediction is going to be. So he's not ready yet with the predictions but we're

going to go

to him in just

a little while.

As Collingwood was telling his

audience that UNIVAC was not ready for a prediction, it had in fact

already made one. The business about needing more time was a cover‑up. Unknown to Collingwood, the folks in

Philadelphia had fabricated that story to save face.

A few

minutes earlier, with

only three million

votes counted, an astounding forecast rolled off the electric typewriter

that functioned as the computer's printer. UNIVAC gave 43 states and 438

electoral votes to Dwight D. Eisenhower. Adlai E. Stevenson would capture only

5 states and 93 electoral votes. The odds for victory by the Republican

candidate were predicted by UNIVAC as 100 to one or better in his favour ‑

an Eisenhower landslide.

Computer programmers huddled

around the printer in shocked silence. Throughout the campaign, pollsters and

political analysts had been predicting a close election that would not be

decided until the wee hours of the next morning. Yet with only 7 percent of the vote counted,

UNIVAC had gone way out on a limb. Too far, it seemed to those watching the

state‑by‑state breakdown emerge from the printer. What was this? Several

southern states going Republican. That hadn't happened in seventy‑two

years! Something was wrong.

A murmur in the crowd: There

must be a glitch in the program. Then a mad scramble. Everyone, grabbing code

books and programming records,

frantically flicked through reams of data, hoping, by some miracle, that any

error that had escaped notice would now surface and be recognized. But after several minutes of fruitless page

turning, punctuated by answering telephoned appeals from New York to get

UNlVAC's act together, the search was called off.

Arthur F. Draper, Remington

Rand's director of advanced research and the man in charge of

election night operations in Philadelphia,

agreed with his advisers that something drastic had to be

done to bring UNIVAC back to its senses. They decided to go right to the heart

of the matter and arbitrarily change the factor‑so carefully fine tuned

through months of preparation‑that extrapolated the number of returns

actually received into estimated final totals for each state. Fortunately, this was a simple

procedure. One merely had to run the program to the breakpoint where the

critical factor was computed, stop the run, type in a new figure from the

supervisory control desk,

and resume processing. Within two minutes, a new set of

totals began rolling off the printer. A chastened UNIVAC reported 18 states and

317 electoral votes for Eisenhower. Much

better, but not good enough for the thoroughly shaken crew in Philadelphia.

Still hedging, they tweaked the

formula again. This time UNIVAC called the election a toss‑up. It gave

twenty‑four states to each candidate with Eisenhower leading in electoral

votes by a scanty margin of 270 to 161. Breathing easier, and wiping

perspiration from foreheads, the computer people in Philadelphia released these

figures to CBS, which broadcast them on the network at 10:00 p.m.

By 11:00 p.m., however,

Eisenhower votes were rolling in like a tidal wave, and UNIVAC, shrugging off

the dampening influence of the twice‑revised formula, swung back again to

the original prediction of 100 to one odds in favour of the general. At

midnight, in his recap of the evening's coverage, Collingwood asked Draper what

went wrong:

COLLINGWOOD: An hour or so ago, UNIVAC suffered a

momentary aberration. He gave us the odds on Eisenhower as only eight to seven

. . . but came up later with the

prediction that the

odds were beyond

counting, above 100 to one, in favour of Eisenhower's election. Let's go

down to Philadelphia and see whether we can get an explanation of what happened

from Mr. Arthur Draper. Art, what happened there when we came out with that

funny

prediction. DRAPE.R: Well, we had a lot of troubles tonight. Strangely enough, they were all human and not the machine. When UNIVAC made it's first prediction, we just didn't believe it. So we asked UNIVAC to forget a lot of the trend information [concerning previous elections], assuming that it was wrong.... [but] as more votes came in, the odds came back, and it is now evident that we should have had nerve enough to believe the machine in the first place.

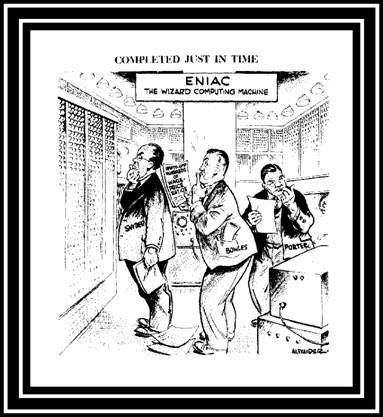

With less than 7 percent of the vote tallied at 9:00 p.m on election

night, UNIVAC gave 438 electoral

votes to Dwight D. Eisenhower and 93 to Adlai E. Stevenson. When the final count was in and the electoral

college convened several weeks later, the official total was 442 for Eisenhower

and 89 for Stevenson.

Many who had believed resolutely in the

superiority of man's intellect now harboured doubts. A machine, a computing

machine, had confounded the experts And

a new word, UNIVAC, which when uttered would conjure up fear, awe, or

disdain, had become a prominent fixture in the American vocabulary. |

|||||